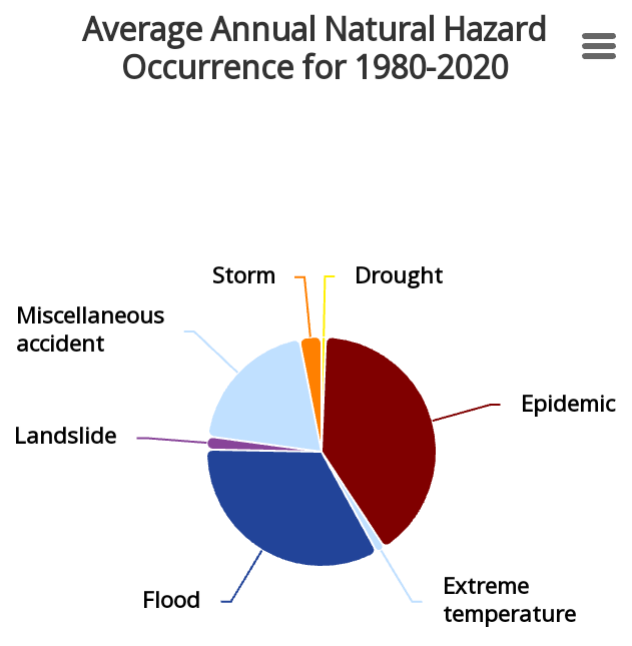

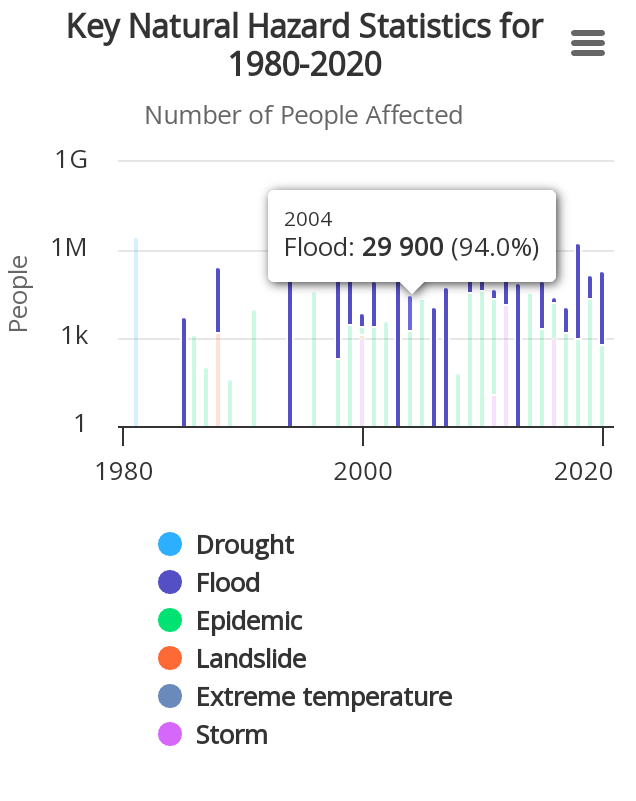

Almost every day, humanity confronts emergencies in forms of natural and man-made disasters. Disasters are so named because of the scale of impacts on human lives and environment, property, finances and future.Earthquakes, landslides, floods, rainstorms, disease emergencies, among others have become the usual disastrous events in human history.

As summarized by CRED, a body tracking disasters, “in 2022, the Emergency Event Database EM-DAT recorded 387 natural hazards and disasters worldwide, resulting in the loss of 30,704 lives and affecting 185 million individuals. Economic losses totaled around US$ 223.8 billion. Heat waves caused over 16,000 excess deaths in Europe, while droughts affected 88.9 million people in Africa. Hurricane Ian single-handedly caused damage costing US $ 100 billion in the Americas.

Join our WhatsApp ChannelThe human and economic impact of disasters was relatively higher in Africa, e.g., with 16.4 % of the share of deaths compared to 3.8 % in the previous two decades. In addition, droughts impacted 88.9 million people in six African countries (the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Sudan, Niger, and Burkina Faso) in 2022. Notable drought events also occurred in China (where 6.1 M people were affected, costing damage worth US$ 7.6 B), in the USA (US$ 22 B), and in Brazil (US$ 4 B). The impact of disaster was relatively lower in Asia despite Asia experiencing some of the most destructive disasters in 2022.”

Nigeria is known for disasters such as landslides, insect infestation, floods, drought, soil erosion, and oil spillage. This is addition to man-made disasters such as building collapse, sectarian violence, all types of accidents, food shortages, climate induced heat waves due to deforestation and oil exploration.

The 2022 floods in Nigeria killed over 600 people and displaced at least 1.4 million people, with over 2,400 human injuries. More than 82035 houses were damaged, while 332,327 hectares of land were affected.

Media Reportage of Disasters

Media reportage of disasters has been an interface between news values, government policy, profit motives, and the professional and ethical requirements of practice. Press historians say that traditionally the Nigerian media have experienced “mixed fortunes” because they operate in a complex environment where they are often accused of not living up to expectations as watchdogs in society. Underreporting, playing politics with disasters, panic-inducing news, lack of prominence, underestimation of social problems and lack of in-depth reporting are some of the problems noted so far in studies on newspaper reportage of disaster situations, e.g., health emergencies. Mbamalu in 2020 found that newspapers focused more on politics of the outbreak of the Ebola Virus Disease in 2014 than on the actual threat of the virus.

Brief on Ethics

Every profession has a code of ethics to guide its practitioners. As noted by the NUJ: “Journalism entails a high degree of public trust. To earn and maintain this trust, it is morally imperative for every journalist and every news medium to observe the highest professional and ethical standards. In the exercise of these duties, a journalist should always have a healthy regard for the public interest.”

Ethics is a branch of moral philosophy, which provides the standards for judging the rightness or the wrongness of human actions. Some ethical principles speak about the absolute nature of ethics in which something is either right or wrong regardless of the circumstances. In other cases, there is situational ethics, which demand contextual clues to judge the acceptability of a course of action.

READ ALSO: Polaris Bank Media Seminar: Expert Calls For More Training On Investigative Journalism

Newstide Board Approves Journalism Mentorship Project In Five Universities

UNN Benefits As Prime Business Africa Kick-starts Journalism Mentorship Project

Journalism ethics include editorial independence, accuracy and fairness, privacy, privilege / non-disclosure, decency, discrimination, reward and gratification, violence, children and minors, access to information, public interest social responsibility, plagiarism, copyright, press freedom and responsibility. Some of these principles such as privacy and non-disclosure are expected to be applied in the context of public interest.

Journalistic Ethics in the Pressure of Disaster Reporting

For journalists, disaster in itself is a news value, and the more disastrous it is, the more it is great news, with high promises of profiteering. But, there also lies the caveat. The fast pace of some occurrences allows journalists little time to develop news as it breaks. Rescue agencies also have little time to share information with journalists. The latter face substantial threats to their lives when disasters involve life-threatening conditions such as chemical leaks and earthquakes.

The grief of survivors, victims and their loved ones as well journalists looking for information often put enormous pressure on rescuers who are always criticized for poor emergency readiness. Journalists themselves face some pressures in answering questions from the relatives of disaster victims. Journalists are thus often criticized for providing sketchy details, especially because they rely on second-hand and eyewitness accounts to report disasters.

Journalists in Nigeria often complain of serial government influence in their report of disasters in terms of fatality, emergency readiness, rescue operations and the circumstances that fertilize disasters such as poor building construction ethics. In the midst of it, journalists also face the professional questions of preserving the truth, insisting on the facts, remaining fair, balanced and accurate. Even when they are able to do this, they still sift through their information for the following reasons:

- To preserve the truth and facts

- Avoid information that may stigmatize victims, or that may put undue spotlight on some ethnic groups,

- Refrain from severally injuring the reputation of rescue workers and government efforts

- Avoid volatile messages that may cause sectarian violence.

- Expunge conspiracy theories, half-truths, unverified information and misinformation.

In the circumstances, journalists must keep in mind the professional and social responsibility demands of disaster reporting, i.e., to provide a comprehensive picture of an occurrence in contexts that enhance understanding, allow for robust public discussions and that presents a representative picture of the segments of society. It also includes information that educates the public on how to report disaster risk factors and how to verify information in an era when the social media dishes out a plethora of unfounded information.

As a caveat, journalists should resist unnecessary pressures to spread unconfirmed reports such as fatality figures. They should always recognize the central issue in disaster reporting. That is, to convince citizens to protect themselves during disasters and to shun rumors, misinformation and conspiracy theories that disfigure reality about disaster situations.

The Case of Covid-19

During the Covid-19 pandemic, which was a health emergency, journalists severely complained about restrictions on access to information. Government always cited the provisions of the journalism codes on protection of, and access to, victims. For example, Section 4.6, subsection 4.6.1, articles ‘a, b & d’ of the NBC Code read:

A Broadcaster shall: a. respect the right of everyone to privacy; b. protect the sources of information in line with The Code of ethics for journalism; c. ensure that a person inadvertently appearing in a scene is not portrayed in a manner to cause him or her embarrassment.

Section 5.4 says that a broadcaster shall (a) “present news and commentary on a crisis or emergency in a professional manner, and, (b) at all times ensure the coverage of a disaster or crisis is aimed at overall public safety.” Some researchers who studied Covid-19 information protection in Nigeria found out that government’s protection of information forced editors to report stories without ‘human face. That is stories showing the suffering of victims and how the healthy should protect themselves and be convinced that Covid-19 was real. The researchers therefore highlighted the need to distinguish between physical privacy, information privacy and related concepts (such as confidentiality and secrecy) in the enforcement of health information privacy. This is to avoid sacrificing the public’s right to know in the guise of health information protection and the ethical requirement of privacy.

Accordingly, some public commentators insist that the following report by The New York Times did not have information that could lead to any form of stigmatization, yet it portrayed indelibly instructive images to the audience. Thus, on May 24, 2020, The New York Times showed how journalism can positively impact the fight against emerging infectious diseases (EIDs), even when the subject matter concerns death. On pages 1 and 12, the newspaper listed names and addresses of 1,000 out of nearly 100,000 Covid-19 deaths in the US at the time. ‘They were not just numbers in our list, they were us,’ said The New York Times, which had something to write about each one of the dead. They got names, age and one special attribute about the dead as shown in the following example:

There was a Nigerian, Bassey Offiong, 25, from Michigan who “met the worst in people but brought out the best in them.” Or Frank Gabrin, “an emergency worker who died in husband’s arms.” Fred Grey who “liked his bacon and hash browns crispy,” Dante Flagello who’s greatest achievement was “his accomplishments with his wife.” There were firefighters, storekeepers, people who brought smiles to people, a grandma who sang every school year to his grandchildren, a woman was in her church choir for 42 years.

Interestingly, a Nigerian newspaper once illustrated a Covid-19 story with an internet picture of a functioning isolation center published by The New York Times on April 16, 2020 (Figure 1). This signified an understanding of the need for such pictures, which unfortunately were hardly published in Nigeria (Figure 2). As noted, absence of such pictures may have caused widespread skepticisms towards Covid-19 in Nigeria.

Some Suggestions

Reporters work within the limits of available information and the influence of other factors such as news values, news sources, social pressures (from owners, government, advertisers) competition, profit motive and the predilections of editors. As such, reporters showed be careful not to cause panic during disaster reporting given that information overload and panic news are contexts affecting both the media and the audience in the reportage of disasters. While the journalists is faced with little time to contextualize fast breaking news, the audience often shields themselves from the trauma of disaster news. Therefore, the media should learn to develop a list of topics that are prone to disaster such as floods and health emergencies. From time to time check their list of disaster-related topics and schedule reporters for updates. Given the landmark roles played by government, NGOs, health workers and the media in the fast-track approach to EVD in 2014, there may be a need for a social strategy for synergy between stakeholders to be worked out and mainstreamed into policy and ethics of disaster reporting.

As it is, individual-medium approach to reporting health disasters may not be enough. As a professional union, journalists should get together and package their needs to government, or the government and the media forge an alliance that helps to define the focus of coverage. Lack of such alliance makes it look as if journalists work for themselves instead of working for their establishments and for society.

In terms of health disasters, for instance, the WHO advises governments to support the media towards “providing financial, technical, and scientific assistance” and that “governments, nongovernmental organizations, and academic institutions should make efforts to support media training in relevant scientific concepts and techniques for communicating risk information without raising unnecessary alarm”.

Dr Marcel Mbamalu is a veteran Journalist, Editor and Publisher

Follow on Twitter: @marcelmbamalu

Phone/Whatsapp: +2348094000017

Email: marcelmbamalu2@gmail.com

Dr. Marcel Mbamalu is a communication scholar, journalist and entrepreneur. He holds a Ph.D in Mass Communication from the University of Nigeria, Nsukka and is the Chief Executive Officer Newstide Publications, the publishers of Prime Business Africa.

A seasoned journalist, he horned his journalism skills at The Guardian Newspaper, rising to the position of News Editor at the flagship of the Nigerian press. He has garnered multidisciplinary experience in marketing communication, public relations and media research, helping clients to deliver bespoke campaigns within Nigeria and across Africa.

He has built an expansive network in the media and has served as a media trainer for World Health Organisation (WHO) at various times in Northeast Nigeria. He has attended numerous media trainings, including the Bloomberg Financial Journalism Training and Reuters/AfDB training on Effective Coverage of Infrastructural Development of Africa.

A versatile media expert, he won the Jefferson Fellowship in 2023 as the sole Africa representative on the program. Dr Mbamalu was part of a global media team that covered the 2020 United State’s Presidential election. As Africa's sole representative in the 2023 Jefferson Fellowships, Dr Mbamalu was selected to tour the United States and Asia (Japan and Hong Kong) as part of a 12-man global team of journalists on a travel grant to report on inclusion, income gaps and migration issues between the US and Asia.

Follow Us