(Remarks to Diaspora group stylized from a chapter in forthcoming Book: How Politics Impoverished Nigeria)

Starting out with faith in Federalism as the best form of political organisational structure for plural societies, to maintain unity in diversity, Nigeria’s post-colonial journey has however been riddled with troubles, of not only unity but of economic performance. Today the state is more or less prostrate. Hardship is rife and palpable. Corruption is so pervasive, how much is involved has stopped to shock, and people in power are physically and emotionally detached and distant from the ordinary people. Public policy reflects poorly the desperate needs of the people and serves more a propaganda value. How can such a situation be remedied.

Join our WhatsApp ChannelMany, including Dr Mike Ajogwu (SAN) have investigated the impact of federalism on national unity. But seldom interrogated is the impact of structure on the culture or values of a society and now this shapes national wellbeing.

The following discussion looks to explore how structure, culture and institutions act as interdependent variables to shape performance.

To establish the dynamics of the influence process which has produced dysfunctions in the nature of the state we turn to too much regarded postulations on culture and performance. Peter Ekeh’s two public’s and Daniel Patrick Moynihan’ two truths and how together they explain why and how Nigeria is failing and how they harbor prescriptions for salvage.

In 2018 Nigeria found itself wearing some awkward toga. A Brookings Institution’s study had found the number of the absolutely poor in Nigeria to exceed those in seven times as populous India. In that same season a Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation study also projected that Nigeria and Congo DRC would, together, soon be home to 40 percent of the world’s poorest. That these studies did not generate urgency driven by a sense of shame in the Nigerian political class tells the story of tragedy foretold.

This was a stark contrast to the promise of Nigeria at Independence when manufacturing as share of GDP was surging, the cash crop economy was relatively healthy and oil exports were on the horizon, and the Nigerian Federation stimulated competition on who would most bring progress to their people between the Regional Governments which administered clusters of ethnic nationality groups as sub nationals with a fair amount of autonomy.

READ ALSO: We Don’t Have Real Political Parties Driving True Democracy In Nigeria – Utomi

What precipitated Nigeria’s drop from the time of the promise of independence, through a season of strategic relevance to one of mediocre performance?

In top flight the Eagle of Nigeria was formally considered a frontline state in the fight for decolonisation of Southern Africa, even from its North West Africa location but it is today down in current standing in World affairs with the perception of being a fragile state with widespread violence, high levels of unemployment, the world’s highest number of out of school children and prolonged periods of universities being closed from strikes by academic staff. Yet its leading political actors swagger and focus on fitting Presidential Jets and Yacht as well as protocol motorcades like spoilt children in a toy shop even as famine looms in the land.

How did Nigeria get to be so dysfunctional and what is there to be learnt from the travails of the evolution of the country’s federalism for the dysfunctions.

Drawing from the literature in several disciplines including Political Science, Economics, Sociology, History and Management Sciences I propose to use two sets of propositions, the two publics, offered by Peter Ekeh and the two truths, proposed by Daniel Patrick Moynihan to interrogate how trends in the operation of the Nigerian Federal arrangement sent the performance of the Nigerian state South bound and has resulted in severe dysfunctions. The central question here is how the intersection of culture and politics explain the ups and downs of Nigerian Federalism and state effectiveness.

The Journey To Serfdom – A Straight Tale

How did Nigeria start out with great prospects for prosperity, rise to seek a place in what erstwhile foreign minister, Bolaji Akinyemi proposed as a concert of medium powers, then slump to poverty capital of the world?

As colonial rule began to approach its end, self-government placed principal responsibility for public choice in the hands of Nigerians by 1957.

This set off competition between the regions for progress perceived as denied the people by the colonizers. One of the first effects was with industrialization. Drawing strategy from Raul Prebisch’s import substitution industrialization idea which Pius Okigbo notes was domesticated into the region with Arthur Lewis industrialization of the Gold Coast. The competition to lead in industrialization would prove the nature of the culture inspired by the structure.

The politics and economics of this competition between ethnic nationalities for material progress and development which Robert Melson and Howard Wolpe refer to as competitive communalism was advanced by political parties that drew their support majorly from the different regions, with the NCNC in the East, Action Group in the West, NPC in the North where it contended with Northern Elements Progressive NEPU (largely around Kano) and the United Middle Belt Congress (UMBC) in what was then the middle belt, but in, more recent geographic expressions would be known as the North Central today.

From independence on October 1 1960 the intensity of rivalry of these parties whose origins Richard Sklar capture quite well in his book, Nigerian Political Parties, had resulted in violent and disputed election outcomes. Remi Anifowoshe provides rich insights into the pattern of this violence in his book on Violence and Politics in Nigeria.

These early days of Democracy in nascent Nigeria, marked by the forging of alliances were marked by ethnic distrust and struggles in early class formation, a phenomenon well explored by Larry Diamond in his study of Class, ethnicity and democracy in the failure of Nigeria’s first republic.

Identity politics defined and dominated political arena following independence in 1960. This Freedom which was secured on the back of constitutional conferences had resulted in a Federal constitution as the grand norm.

In spite of these failings which resulted in a civil war post 1970 Nigeria re-ignited the promise of 1960 of a prosperous society in which though tribe and tongue may differ, as the national anthem proclaimed, the people toiled together in brotherhood.

How did Nigeria come from great promise to one in which the pressure to emigrate is so high. Clearly understanding may be enhanced by what is more or less a straight narrative of political and economic developments since independence, as context for a more analytic presentation of the same history to enable an explanation of how the state became so dysfunctional, especially with a view to locate how structure of the federation may have had an effect on conduct. So let us begin with the straight tale.

The predominance of three ethnic nationality groups helped provide anchoring for the federating of the more than two hundred and fifty different linguistic groups in the country and so three regions built around the Yoruba in the West, the Igbo in the East and the Hausa-Fulani emerging fusion from Fulani conquest of the Hausa states and organising of the area into emirates within Fulani rulership became the basis of federating units. This meant that the question of minority rights and minority group agitation within these blocks would become a major feature in the issues of nation building.

READ ALSO: Nigeria Is Not Working – Pat Utomi

The post independent tensions rooted in the policies of Nigerianization in colonial times as better educated Southerners seemed poised to dominate the Northern Nigeria public service. The 1954 statement of the then chairman of the Northern Nigeria Public Service Commission Abubakar Imam that Nationalization would mean replacing the red white men with the black white man (southerners) were pointers to the frictions that would manifest after independence.

The friction covered territory like Industrialization, Education, Agriculture infrastructure and media of communication. I will start these illustrations with how the regions competed in the media ownership space.

Media and Competitive Communalism

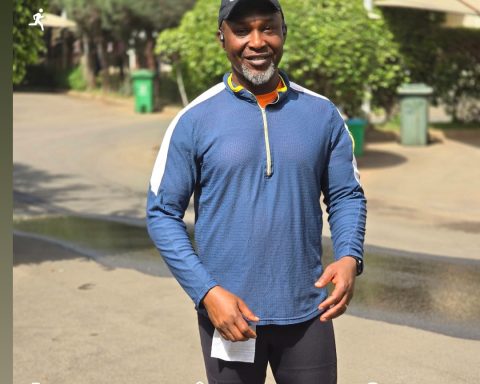

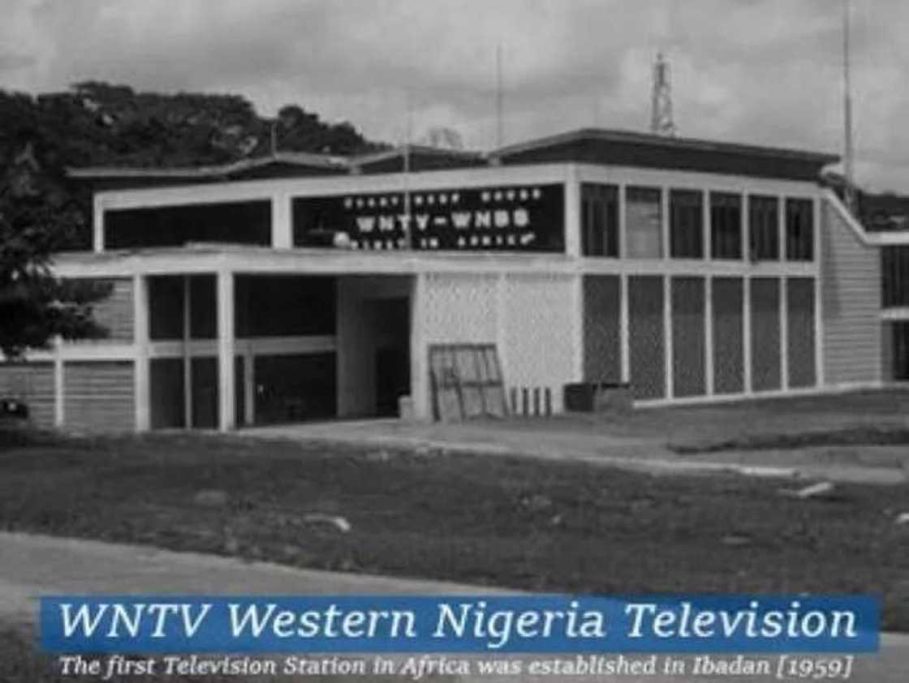

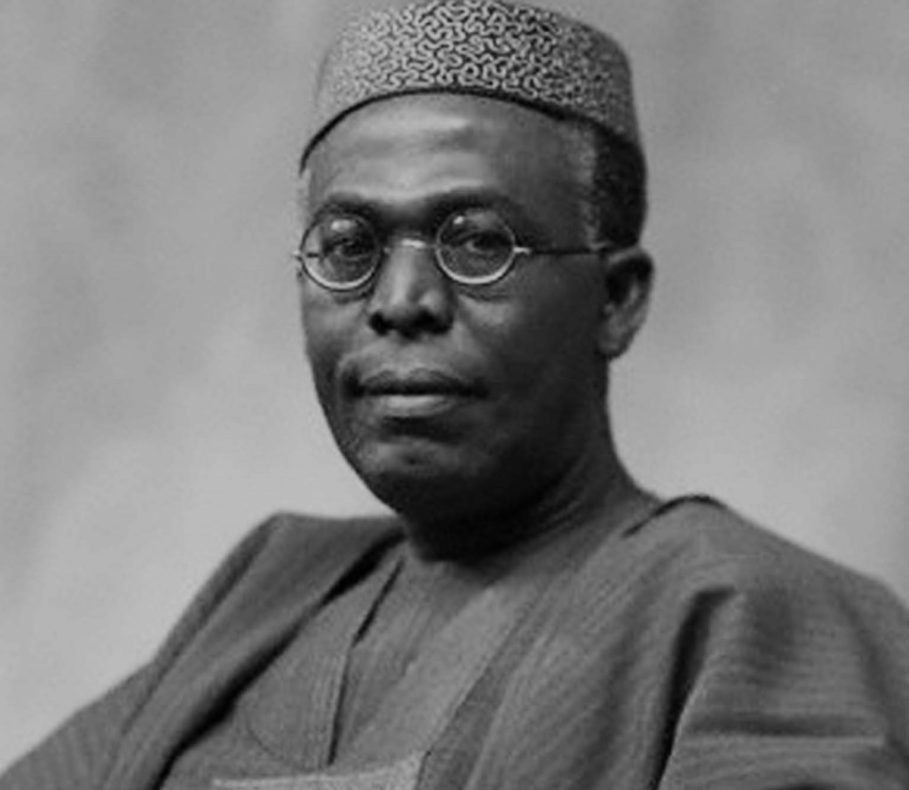

The early battle ground of competitive communalism and identity politics was the fight for mind share and influence over the people through means of Mass Communication. When in the era of self-government, the federal government owned Nigerian Broadcasting Service reported, unfavourably, the actions of the Premier of Western Region, Chief Obafemi Awolowo and he sought access to respond and was denied, he decided to set up his own broadcast service. He chose to leap frog radio to a new emerging technology called television. In so doing, Ibadan, the capital of the western region became the first city in Africa to have a television station. It got there ahead of several European capitals like Dublin and Brussels.

The Eastern Region followed quickly and then the North with Radio Kaduna Television (RKTV). Such was the rivalry that WNTV announced itself with the words ‘First in Africa’. As a secondary school student in Ibadan in the 1960s I was used to the payoff line: WNTV-First in Africa. The Eastern Region’s broadcasting service would respond quickly with its own TV station, announcing itself as ‘Second to None’.

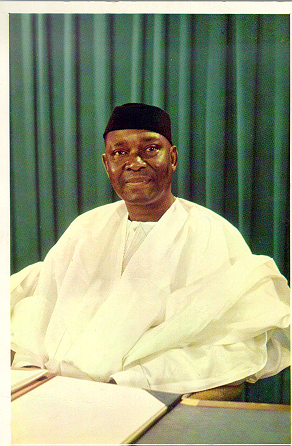

In many ways the media of communication, through privately owned newspapers like The West African Pilot owned by Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe, leader of the NCNC and Premier of Eastern Region; the Nigerian Tribune, owned by Chief Obafemi Awolowo of the Western Region.

The media would become very partisan, in the main, and fan embers of group antagonism in the elections crises of the early 1960s setting the stage for a military coup d’état in January of 1966.

This rivalry was even more evident in the desire to create jobs and economic growth through attracting investments into manufacturing.

Manufacturing

One of positive outcomes of the Federal structure of the Nation’s consensus on Federalism was the quick spread of manufacturing as a result of the competition of competitive communalism. When the Western region established the Ikeja Industrial Estates and the East followed with the Aba and Trans Amadi (Port Harcourt) and the North with Kakuri in Kaduna which remarkably became the textile hub for Nigeria that would seek to optimize the cotton endowment of the region.

As it would turn out the Hong Kong Chinese who set up in Kaduna would be export to Europe from their first production. Irene Sun, a China export at Mckinsey who heads the team watching Chinese manufacturing’s second wave into Africa captures the early triumph of those Kaduna Mills in her book Africa. The world’s next factory.

The rivalry had as part of its effect the relocating of Pfizer from Ikeja to Aba.

A few years after, the ‘dangerous alchemy of soldiers and oil’, arrived with Military rule beginning the centralization of power and authority in Nigeria as oil became a central contributor to the Distributable Pool fund, federally collected revenues for fiscal transfer among federating units. A combination of factors that include Dutch disease, from the management of oil revenues and Trade policy triggered de-industrialization in the infant manufacturing sector that Nigeria still was Jerome Udoji, the first indigenous Permanent Secretary in Eastern Nigeria recalls in his memoirs how the premier of Eastern region, Michael Okpara set off in search of European investments in manufacturing not to be outdone by Western Region.

Education

With the recognition of the better politicians around the world that the social sectors of Education and health care were key to development the race for education became as historically significant as the race to Nikki between France and Britain to reach Borgu kingdom and sign a trade agreement with the leaders.

From shifting cultural norms captured by Chinua Achebe in the iconic novel Things Fall Apart the Igbos came to value education early in the contact with the colonizers. But the west got quickly ahead.

It started with free education with ambitions of universal free primary education. The premier of Western region, Chief Obafemi Awolowo had made the policy call. Dr. Azikiwe, anxious his rival now premier in Eastern region was universal meal for free primary Education policy for Eastern region.

The premier got push back from the then newly appointed Permanent Secretary for finance in Eastern Region, Chief Jerome Udoji whose team thought the region could not afford universal free primary education and recommended fees for primary class 1 and 5. Chief Udoji details the crisis that followed, his threat to resign and proceeding on leave to the UK in his memoirs: Under Three Masters.

Education would make the concurrent list in the constitutional deployment of roles and duties to levels of government, national and sub-national, come alive at independence. At the Federal level the government of Prime Minister Tafawa Balewa set up the committee on Higher Education under the Chairmanship of Oxford Educator Sir Eric Ashby but the government of Eastern Nigeria had gone ahead to set up the University of Nigeria, Nsukka which became the first indigenous University in Nigeria as the University College in Ibadan was still a College of the University of London. Sir Eric Ashby whose commission recommended the founding of the next generation of Nigerian Universities had remarked at the time that the quality of Higher Education in Nigeria was as good as the very best in the World.

One generation later, things had gone south with Nigerian Universities which seemed perennially hunted by strikes.

Political crises, especially around elections, census charged with being rigged to provide advantage, religion and treason trials, with the rioting that came with the disputes, drove the country into a coup d’état in January of 1966.

The military rule which altered the structure of the Federation deserves close consideration.

For the sake of brevity I will skip my straight tale narrative of Military rule which I treat in much detail both in the book in progress from which some of these insights are drawn (How Politics underdeveloped and Impoverished Nigeria) and in another volume, an anthology of Leadership in Nigerian History, with other authors where I have been assigned two chapters on SAP and President Babangida. Here, I will only point to how the ‘dangerous alchemy’ of soldiers and Oil resulted in the centralization of the structures of government with Generals at the center basically handing out prebends to Colonels running the sub nationals. This phenomenon evolved into what Richard Joseph so well captures in the idea of Bureaucratic Prebendalism and the prebendal state where the rush became how to share the ‘national cake’ baked by none. This arrangement led Nigeria to a classic tragedy of the commons as postulated by Garrett Hardin in that seminal 1968 essay.

READ ALSO: Economic Crisis: Nigeria Has No Option Than To Produce For Food Security, Forex Stability – Utomi

Oil which was found in commercial quantities in Oloibiri in Eastern Region in 1956/57 had increased its contribution to national revenues significantly after the civil war, especially following the Yom Kippur Arab- Israeli war of October 1973. When the Arabs cut off supplies to perceived supporters of Israel and scarcity resulted in quadrupling of crude oil prices.

The development of military rule and oil price hikes converged to produce the phenomenon of prebendal politics, as Richard Joseph coined it.

The two Truths, two Publics, and Federalism In Nigeria

The objective of this essay is essentially to explore the nexus of culture and structure in the determination of development, economic performance and human progress. In the general and analytic tracking of the evolution of Nigeria up till 2022 we have shown the evolution of such structural patterns as a structure of government following the constitutional conferences of the 1950’s that gave the people a Federal Westminster Parliamentary form in which fiscal transfer were between a central and a subnational level of government, with exclusive and concurrent legislative lists. But military rule centralized authority and chipped away at subnational scope during a long season of military rule.

By the middle 1970s the reforms of the Obasanjo administration had brought into the fiscal transfer arrangements a third level of government, the local Governments.

On the side of culture, we had seen it evolve from competing ethnic nationality groups trying to get ahead of the others in the early days of self-government and Independence when politics was defined by the simple life, frugal and more accountable governance. There was the flamboyance of the Okotie-Enoch’s but generally politicians lived the simple life. Back then culture was also strong on the cult of personality with political leaders. With military rule culture became more prebendal, accountability declined in the face of state capture and corruption laced with impunity become the routine

Encouraged by culture of the age of money, in which revenues and the effects on the economy buoyed a tradition of conspicuous consumption of people in public life, the public sphere became much identified by behavior which resulted in much public resentment of democracy as evidence from longitudinal data of the Afro barometer series show clearly. Citizens became less positive about the value of democracy and voter apathy increased. INEC data on voting showed less and less participation even with population increasing. Would government be closer to the people in a more Federal state in which the sub-national were the epicenter of development and progress and policies be more people centred and growth oriented?

This is why we turn to two legendary intellectual statements about culture and political conduct for insights we could use to interrogate the nexus of culture and structure in questioning how Nigeria’s Federalism has journeyed and what the imperatives for going forward could be.

The Two Truths

In summer of 1998 the Harvard Academy for International and area studies chose to explore the connection between culture, political, economic and social development, chiefly with respect to poor countries’ as Lawrence Harrison writes in the introduction of the book Culture Matters. How values shape Human Progress. The colloquium reported on in the book was significantly stimulated by some profound words by former Harvard Professor and intellectual in public life who served as US Federal cabinets and finished his career as a US senator from New York, Patrick Daniel Moynihan.

Co-editor of culture matters, with Lawrence Harrison, Samuel P Huntington states thus;

Perhaps the wisest words on the place of culture in human affairs are those of Daniel Patrick Moynihan- ‘The central conservative truth is that it is culture, not politics that determines the success of a society… The central Liberal is that politics can change a culture and save it from itself.

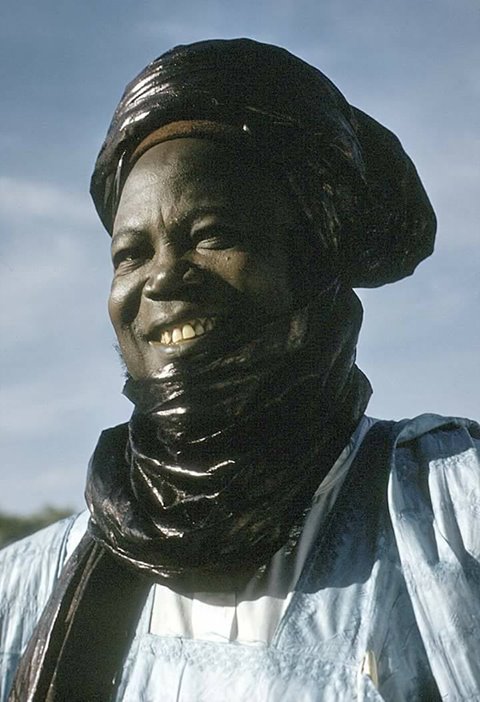

The colloquium by the Harvard academy was to explore the truth about the two truths. So how have liberals in Nigeria, and politicians that are not conservatives tried to engineer culture, and its conservatives tried to drive certain values, and how these thrusts have manifested in the structure of the Nigeria Federation. In ways the liberals among the founding fathers were Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe (Zik) and Chief Obafemi Awolowo. The clear conservative was Sir Ahmadu Bello, the Sardauna of Sokoto.

On the cultural differences of multiethnic Nigeria the liberals like Zik sort a melting pot. This was pushed back on by the conservative Ahmadu Bello. Both Zik and Awolowo agreed on social engineering but differed on how.

Awolowo would appear the most Federalist of the three in regional policies but his move from the region where he was premier to the centre as opposition leader suggests a determination for re-engineering Nigeria on ethnic, and geographic spatial disposition of Nigeria, the anecdotal counterpoint from Zik and the Sardauna, exampled cultural influences on how the structure of the country is affected by culture and that structure shapes the evolution of culture.

While Zik is said to have called for setting aside or overlooking the differences to forge ahead in unity, the Sardauna called for putting those differences on the table so they can be understood.

A Federal structure became a path forward in which groups could make progress at their own pace.

When military rule succumbed to its organisation form to centralize power, that structure, relative to how people behave in situations of concentration of power, the reason for doctrines of checks and balances, unfortunately gravitated towards state capture, poor observance of rule of law, and systematic corruption.

It is noteworthy that while a more conservative Northern political class continue to hold on to a not so-Federal arrangement of the 1999 constitution promulgated by the military in 1999, without input from the people, even though the open statement ‘falsely’ says ‘we the people’ the southern middle class, with those from the middle Belt and Northern minorities of the Northwest and Northeast, have been calling for “true Federalism”.

But will “true Federalism” reduce the widespread corruption and return governing to a “competitive communalism” type focus on the common good of the ethnic nationalities of the subnational units of government.

Peter Ekeh’s navigation of his way through civic and Primordial cultures could aid understanding.

READ ALSO: Between Creation Of More States And Regional Govt, Which Do We Really Need?

But the lesson from two truths for governance in Nigeria is that liberals have tried to engineer both culture and structure for greater governance effectiveness. Even though Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe and Chief Obafemi Awolowo were clearly liberals and tried to engineer change through policies on education and public enlightenment. It was General Ibrahim Babangida as military head of state that made the most structured effort at social engineering regarding political parties, ideology, and the structure of the federation. He set up a political bureau and institutions to guide the social engineering effort majorly through, the centre for Democratic studies which had Prof. Omo Omoruyi as Director General.

Opponents of that liberal social engineering effort either change that the true intention were to waste time and allow President Babangida more time in power or that the results are nowhere. But it can be said that it sowed the seeds of a two-party dominant system compared to the 1960’s tradition of three region based major parties plus major minorities parties in like the UMBC, with NEPU as example of opposition at the regional level to the major party.

The central truth here is that both the conservative in the Nigeria journey suggest a federal arrangement more suitable, to drive culture for those who favour traditional values, a federal arrangement would enable evolution of tradition as suited to the geographical space of a sub-national government. On the other hand liberals would engineer differences at the sub-national level pushing towards convergence.

The Two Publics

In what is much acclaimed seminal article “colonialism and the two publics in Africa: A theoretical statement, published in the Journal of Comparative studies in History vol. 17 no. 1 in January of 1975 Peter Ekeh makes the point that whereas in Western societies one civic public is identifiable, colonial experience in Africa has two public cultures as such. This is derived from the struggle between the colonial and the colonized elites competing for a legitimacy of their authority and influence over the population as the Indigenous emergent classes challenged the legitimacy of the colonizing ruling class.

The one “Public” is primordial and derives from traditional institutional arrangements. The other public, related to the institutions of modernity and the new ways is a civic ‘public’ of the new state was viewed as alien and disconnected from the binding norms of traditional or primordial. This bifurcation of loyalties and institutional boundaries in the two different publics explains the tendency for the same person in the primordial public to act with regard to the common good in a positive way and not act against norms through corrupt enrichment, for example but to act differently in the civic public space so the same man as treasurer for his ethnic group or Town Union Association does not steal a dime would literally empty the Federal Treasury as a Permanent Secretary.

The logic to this is that the closer the modern organisation form is to the primordial base the less likely it is to be afflicted with the high level of goal displacement that makes the modern state in post-colonial Africa so dysfunctional.

This would support the strong sentiment for deepening the principle of subsidiarity and the decentralization of authority.

We can mount up theoretical explanations and evidence for why the conduct of politicians in our unitary structure has taken away from progress but I think we have enough already to make the point that it will serve Nigeria well to recognize that current structure has resulted in a culture of corruption, entitlement and diminished production. An embrace of decentralization it is more likely will be more friendly to desired value and productive advance of society.

You in the Diaspora are privileged from your exposure in your land of sojourn to encourage this new direction of consciousness.

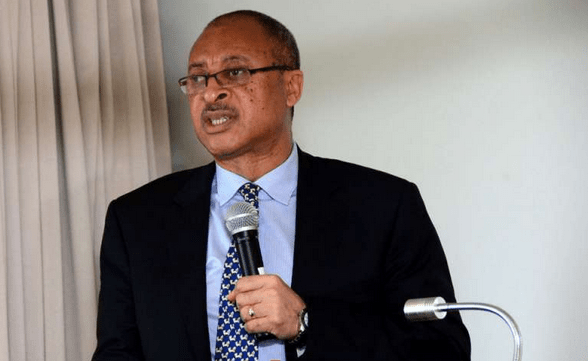

Patrick Utomi is Professor of Political Economy and Entrepreneurship and the founder of the Centre for Values in Leadership.