When the British colonial government introduced the Local Government Ordinance in 1914, the aim was to create a tier of government that would reach to the grassroots. Until independence and beyond, the idea of local government (LG) subsisted, with at least five post-independence reforms since 1976 aimed at strengthening government at that level. In 1988, the then military government scrapped State Ministries of Local Governments, which had given state governors the habit of running local governments like fiefdoms.

LG independence was affirmed in the 1999 Constitution, Section 7(1), which recognised the local government as a third tier of government. The Constitution provides for elected officials to run local councils through chairmen and councilors. LGs are also responsible for providing basic services such as primary education, healthcare, and sanitation. Generally, the roles of LGs include the provision and maintenance of primary, adult and vocational education, the development of agricultural and natural resources other than the exploitation of minerals. Others are naming of streets, numbering of houses, the provision and maintenance of public conveniences and sewage/waste disposal, undertaking the registration of deaths, births, and marriages. Economically, LGs are equally charged with the assessment and collection of tenement rates, control and regulation of outdoor advertising licensing and others.

Join our WhatsApp ChannelHowever, recognition of LGs as a third tier after the federal and state governments has remained amorphous. This is because local governments could not really affirm their independence as a tier of government due to absence of clear constitutional provisions about elections, tenure of officials and finance management. As it is, the Federal Government (FG) allocates funds to the LGs through the states. The states divert the funds to a joint account, from where they dictate what the LGs get. The habit of having state ministries of local governments has not totally left state governors.

READ ALSO: Anarchy: 18 State Governors Won’t Allow Elections For Local Govt Chairmen, Councillors

The Fight for Supremacy in LG Autonomy

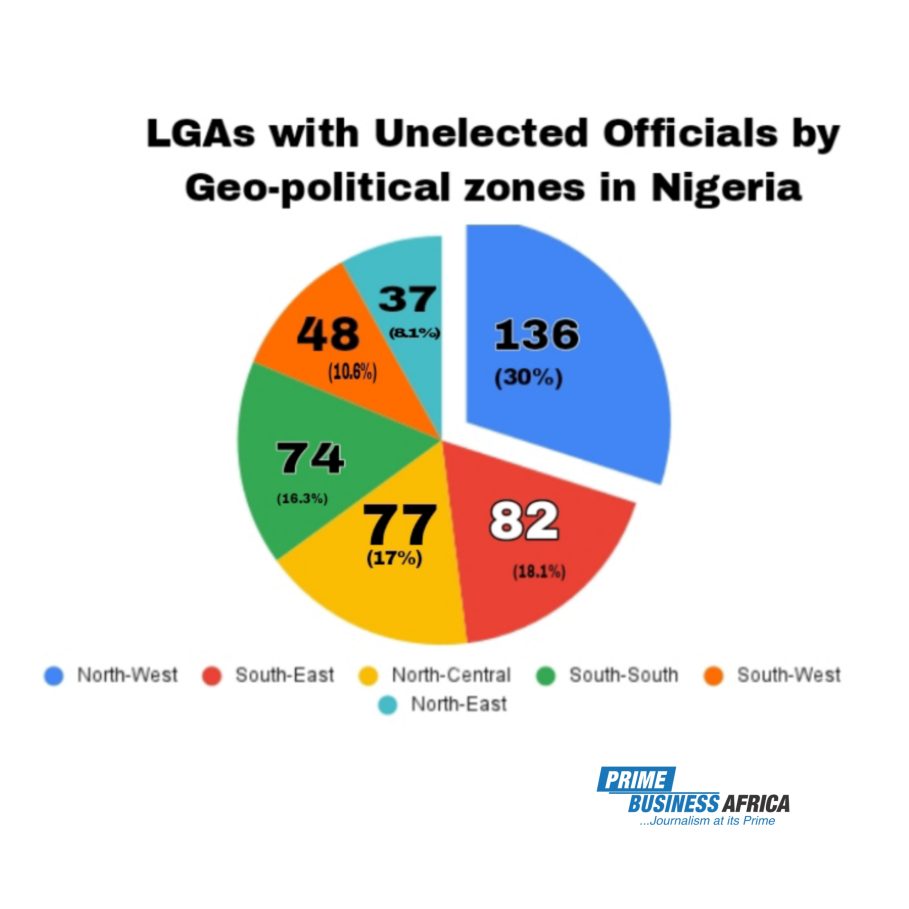

Since the return to democratic rule in 1999, the expression local government autonomy has remained a singsong among Nigerians. Elections into LG offices are at the mercy of state governors, who whimsically disband elected LG officials and set new elections or simply work with self-appointed caretaker administrators. At the last count in June 2024, 20 out of the 36 states in Nigeria did not have elected local government chairmen and councilors. Specifically, at least 454 of Nigeria’s 774 local governments (58.7%) neither have elected LGA chairmen nor elected councilors. Instead, they have caretakers appointed by state governors (Table 1).

Constitutional reforms to liberate LGs from states have experienced multiple sabotages over the years. Section 7 of the 1999 Constitution provides that local governments should be run by elected officials. This law was reaffirmed in 2006 and 2014, when the Supreme Court clarified that governors did not have the powers to sack elected local government officials. More recently in 2019, the Supreme Court also ruled that local government areas without elected officials should not receive federal government allocations. Former President Muhammad Buhari had in the same year initiated the process towards disbursing federal allocations to local governments straight from the Nigerian Financial Intelligence Unit (NFIU). Guidelines were produced to this effect, but they were sabotaged by state governors, who insisted that the NFIU had no legal basis to specify how LG funds would be disbursed and used. The NFIU guidelines require that “transactions from joint local government accounts be restricted, and funds be transferred directly to local government accounts, reducing state government control.”

Buhari signed an executive order in May 2020 to grant financial autonomy to LGs, state legislatures and judiciaries. President Buhari also reviewed the Revenue Allocation Formula, where he proposed a new sharing formula that would give LGs 21.04% of federal allocations. This was an uptick from the current 20.60%. The move however did not come into effect due to the non-completion of a constitutional review process. State governors remained defiant as a result of selfish political control and expediency in terms of winning second terms and controlling LGs decisions and funds.

In line with efforts made to ensure sure LG autonomy, President Tinubu has, since assuming office, sought ways to assure and to upgrade the autonomy of LGs. In late May, Tinubu dragged the 36 state governors to the Supreme Court seeking to (1) stop the governors from direct control over LG funds, (2) stop funds allocations to states without democratically elected LG officials, and (3) stop state governors from unilaterally and arbitrarily removing elected LG officials and running LGs with caretaker committees. As of 13 June, the apex court reserved judgment in the case, having informed the parties that a new date would be communicated for continued trial.

Beyond the Governors, There are Other Genuine Concerns

The history of central/federal government in Nigeria is a history of over centralized controls that have not really benefitted the country in meaningful ways. The country tended to fare far better when the regions had control over their resources. The federal structure has ensured more and more federal/central control over key mineral resources, electricity, banking, security apparatus, education, law enforcement, and now LG autonomy. Federal control over resources has led to unbridled corruption over the years, with dire economic implications, where multinationals siphon the national resources and allegedly facilitate problematic conditions (e.g., arms proliferation) that help them to continue fleecing the country. The story of steel, gold, and crude oil productions and the gory resource control fights by non-state actors across the country are strikingly familiar.

Banking and economic reforms in the country have been allegedly the handiwork of the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and other international bodies to corner Nigeria, and much of sub-Saharan Africa into political and socio-economic strangulation. The Structural Adjustment Programme of the mid-1980s, and similar economic programmes have been accused of being the bedrock of Nigeria’s problems. It is the same with various laws and reforms in the petroleum sector.

Notably, these allegations remain allegations, but they tend to hold water considering how badly the federal government has fared in educational, political and economic governance. The series of industrial disputes between the federal government (FG) and the Academic Staff Union of Universities rest on allegations that the FG was implementing scripts written by the IMF to emasculate education in Nigeria, e.g., the Integrated Personnel Payroll Information System (IPPIS) that caused nearly one year of public university strike in 2022. The same allegations trail the ongoing attempt by the Nigeria Universities Commission to usurp the academic powers of university senates in forcing a national curriculum on universities in Nigeria. Therefore, there are genuine fears that unseen hands may again be propping the FG in its serial dance towards greater LG autonomy.

READ ALSO: Nigeria’s Supreme Court Reserves Judgment On LG Autonomy Suit

First, a fully autonomous LG system may transfer influence from the states to the centre in Abuja, creating a new power base that could bypass the governors in political bargains, e.g. second term and local resource revenues. If the federal government gains control of ordinary things like sand and stones, locals may forgo the unfettered access they have to building materials and funds therefrom. The impact on home ownership by ordinary Nigerians, long deprived of federal housing facilities, can be imagined. This can frustrate governors and threaten the stability of LGs, further confirming the hunch that there is more to insecurity that the FG is willing to admit.

For over 50 years, some non-governmental organisations have promoted inclusion, equality and more direct access and control of local resources by the locals. If well managed, this is a potent mechanism for empowering the locals to take more charge of their environments and the key decisions about their governance. If poorly managed, as is more likely going to be the case in the Nigerian context, it may become a pretext for the NGOs to have unfettered access to local intelligence about local resource potentials of FGs. Around the world, governments in developing countries are beginning to restrict the extent of research funding and activities of NGOs due to perceived dangers such as spying and control of the local populace.

As one analyst put it “Autonomous local governments may be more prone to external pressures and agreements that grant international companies or organisations access to local resources. Decentralization could facilitate neocolonialism, enabling foreign powers to exploit local resources and undermine Nigeria’s sovereignty. Regionalization could facilitate international trade agreements and investments, potentially leading to the exploitation of local resources and labor. Autonomous local governments may be more integrated into the global economy, potentially leading to a loss of local control and sovereignty.” Once again, the Supreme Court, suffering from a historical low in citizen credibility, will hear the case, and Nigerians await its wisdom and opportunity to redeem its most recent credibility crisis.

Conversely, some have also speculated that LG autonomy may smoothen the path to regionalism or more decentralization, bring about better governance of the country by shifting from the current over-centered political structure of Nigeria. In fact, Kwara State governor, Abdulrahman Abdulrazaq is seriously championing full LG autonomy, which he claims to have instituted in his state amidst benefits.

READ ALSO: Between Creation Of More States And Regional Govt, Which Do We Really Need?

As it is, what is necessary is a clear description of the LG system in Nigeria, and this is a function of the ongoing, but lethargic, constitutional reforms. It is not enough to call LGs third-tier government without clearly describing their functions and powers. National Chairman of the Inter-Party Advisory Council (IPAC), Chief Peter Ameh, has lamented the collapse of the local economy as a result of the failure of LGs in Nigeria. He advised that “Section 7 of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (as amended) relating to the place of Local Governments as the third tier of government should be amended to specifically guarantee the existence, establishment, structure, composition, finance, functions and tenure of Local Governments under the Constitution.” He also called for Section 153, 197 and The Third Schedule to the Constitution to be amended to provide for the following: re-designation and re-ordering of States Independent Electoral Commission (SIEC). Electoral reforms, according to Chief Peter Ameh, should (i) ensure that SIECs are incorporated within the structure of INEC, (2) appointment of full-time 774 Local Government Electoral Officers by INEC (3) appointment of full-time career Assistant Electoral Officers by INEC at ward levels.

Table 1: States and Zone Distribution of Unelected LG Officials

| State | No. of LGAs | Geo-political Zones | No. of Undemocratic LGAs |

| Abia | 17 | Northwest | 136 |

| Anambra | 21 | Southeast | 82 |

| Enugu | 17 | North-Central | 77 |

| Imo | 27 | South-south | 74 |

| Akwa Ibom | 31 | Southwest | 48 |

| Delta | 25 | Northeast | 37 |

| Cross River | 18 | ||

| Ondo | 18 | ||

| Osun | 30 | ||

| Benue | 23 | ||

| Kogi | 21 | ||

| Kwara | 16 | ||

| Plateau | 17 | ||

| Bauchi | 20 | ||

| Yobe | 17 | ||

| Katsina | 34 | ||

| Kano | 44 | ||

| Kebbi | 21 | ||

| Sokoto | 23 | ||

| Zamfara | 14 |

Dr Mbamalu, a Jefferson Fellow and Member of the Nigerian Guild of Editors (NGE), is a Publisher and Communications/Media Consultant. His extensive research works on Renewable Energy and Health Communication are published in several international journals, including SAGE.

SMS/WhatsApp: 08094000017

Follow on X: @marcelmbamalu

Dr. Marcel Mbamalu is a distinguished communication scholar, journalist, and entrepreneur with three decades of experience in the media industry. He holds a Ph.D. in Mass Communication from the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, and serves as the publisher of Prime Business Africa, a renowned multimedia news platform catering to Nigeria and Africa's socio-economic needs.

Dr. Mbamalu's journalism career spans over two decades, during which he honed his skills at The Guardian Newspaper, rising to the position of senior editor. Notably, between 2018 and 2023, he collaborated with the World Health Organization (WHO) in Northeast Nigeria, training senior journalists on conflict reporting and health journalism.

Dr. Mbamalu's expertise has earned him international recognition. He was the sole African representative at the 2023 Jefferson Fellowship program, participating in a study tour of the United States and Asia (Japan and Hong Kong) on inclusion, income gaps, and migration issues.

In 2020, he was part of a global media team that covered the United States presidential election.

Dr. Mbamalu has attended prestigious media trainings, including the Bloomberg Financial Journalism Training and the Reuters/AfDB Training on "Effective Coverage of Infrastructural Development in Africa."

As a columnist for The Punch Newspaper, with insightful articles published in other prominent Nigerian dailies, including ThisDay, Leadership, The Sun, and The Guardian, Dr. Mbamalu regularly provides in-depth analysis on socio-political and economic issues.