IT is believed in Igbo land that a successful man is one who has positively influenced the lives of the people around him.

Regardless of how successful one may appear, without their affluence having a positive influence on those around them and beyond, there is little regard for them in Igbo land. It is for this reason that in Igbo land, charity is a timeless index for measuring wealth.

Join our WhatsApp ChannelA person is successful and mature, irrespective of his age when he is the type that extends assistance to others. Charity, in Igbo land, truly begins at home.

Onyeka Nwelue, as an African of Igbo origin, understood this cultural norm quite early in life and made it a habit to empower people around him according to his capacity. Those who know him well can attest that he imbibed this value of charity from when he was yet a child.

In 1997 when he was about nine years old, he became famous in his village for bringing his elders, younger ones, and friends together for storytelling by moonlight. He would come with such gifts as bananas, oranges, udara and whatever fruit was in season to reward those amongst his audience who answered his questions at the end of any story.

Nwelue also extended his juvenile bigheartedness to the Anglican Children Ministry (ACM) and the Children’s Choir of St Paul’s Cathedral in his village, Ezeoke Nsu. As a member of the Children’s Choir, he encouraged other children to attend church and gave them gifts as a reward. Only a few practised the teachings of Nwelue’s teacher, Sir Josiah Nwelue, at the Anglican Children Ministry, as exceptionally as Nwelue did. Sir Nwelue taught his students that a world full of philanthropists will always prosper. He taught his students the importance of charity, drawing examples from the scriptures and everyday lives.

Sir Nwelue often drew parallels between the boy who offered Jesus five loaves of bread and two fish and Nwelue’s juvenile philanthropy. Back then, it was easier for this writer and other kids to relate with Nwelue than the boy in the Bible since we all benefited continuously in some way from Nwelue. Every child knew to come to church because Nwelue was sure to be there with gifts of fruits, sweets and other many things that little children fancied. Interestingly, like Nwelue, this writer and several others grew up to attend Mount Olives Seminary in Umuezeala Nsu. There, he constantly enjoyed the friendship of other students because of his popularity as a teenage philanthropist. His advantaged background and altruism endeared him to several students, including this writer, who benefitted from his beverages and other weekly supplies. Today, we remember how those supplies were our saving grace from the lesser meals served in the refectory.

Beyond food supplies, however, Nwelue was also generous with his time. He would organize students for tutorial classes after school hours, just as he had done as a child telling moonlight stories in his village. In no time, he became recognized as the only student tutor in the seminary, and both junior and senior students benefitted from his tutorials. In one of such classes, he gifted one of his juniors, Anyanwu Timothy, writing materials for being one of the most attentive and punctual students in his tutorials. As he encouraged, his Michael West Dictionary became a primary resource for checking the meaning of new words encountered daily by his students, especially those who had none.

Nwelue would later be appointed the Senior Prefect—the highest prefectorial role—in his fifth year at the seminary. One of his primary achievements as the senior prefect was the creation of the Jet and Press Clubs in the seminary. The Jet Club aided students in the sciences and created prizes for best-performing students in science quizzes. To keep the club operational, he often squeezed money out of his pocket and gave from the little he had received from home. His leadership also ensured that the club got most of its funding from external prizes won during competitions and from levies he imposed on students for misdemeanours. In addition, he encouraged students in the Arts to join the Press Club and set up prizes for best-performing students in poetry, short stories, debates, and quiz competitions. He would later launch enlightenment and entertainment events like the Social Nights of every last Friday of the month and gave prizes to the best-performing groups. These prizes, some of which were self-sponsored, became synonymous with Nwelue’s achievements as the first leader of these clubs.

It is, therefore, the true strength of character that Nwelue’s disposition to philanthropy never ended with his days in the seminary. He has been affecting life positively at both individual and communal levels ever since. Between 2010 and now, Onyeka Nwelue has embarked on travels across tertiary institutions in different parts of the world, volunteering to lecture students without pay. He has visited the Ohio University, University of Johannesburg, Manipur University, University of Lagos, the University of the West Indies, and others to teach voluntarily. He has also served in the English Language Department of the Faculty of Humanities, Manipur University in Imphal, India. His bigheartedness led to his controversial advocacy that no one should teach for any reason other than the genuine passion for influencing the future positively.

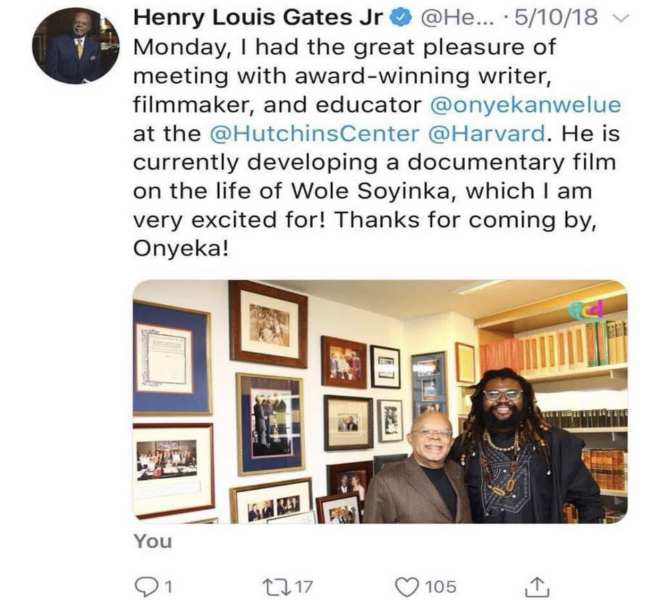

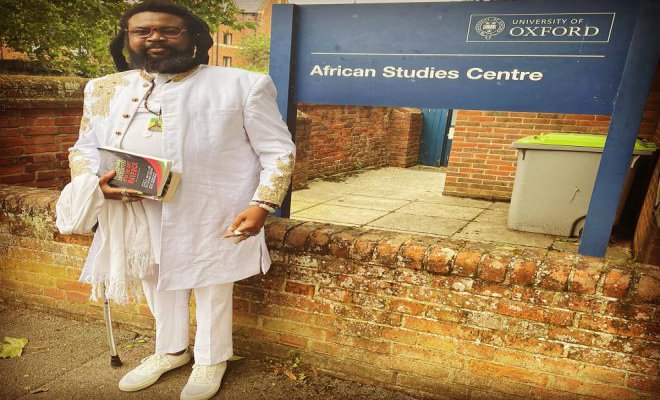

Further, Nwelue recently instituted the annual James Currey Prize for African Literature to recognize and support talented writers of unpublished works of African literature. Nigerian writer, Ani Kayode Somtochukwu, won the maiden edition of the James Currey Prize for his novel manuscript And Then He Sang A Lullaby, receiving 1000 pounds in cash reward and a short residency at the University of Oxford. Nwelue was inspired to create the James Currey Prize because he felt, and rightly so, that the courageous British Publisher, James Currey, was underappreciated. James Currey made it possible for many African literary works of post-colonial Africa to see the light of day when it was most unfashionable. His tireless dedication to promoting African writers through the famous African Writers Series later earned him the title Godfather of African Literature.

Nwelue has assured that no participant in the James Currey Prize will receive preferential treatment. He intends to sustain the rigorous scrutiny employed in selecting the winner of the maiden edition. He is also optimistic that the James Currey Prize would promote the visibility of budding African writers.

In conclusion, therefore, it is apt to say that Onyeka Nwelue, right from childhood, has demonstrated what we may call the new-age philanthropy. And we have no doubt that he will continue in this path, as he has already shown us.

Follow Us