By Deborah Chidinma Chibuife

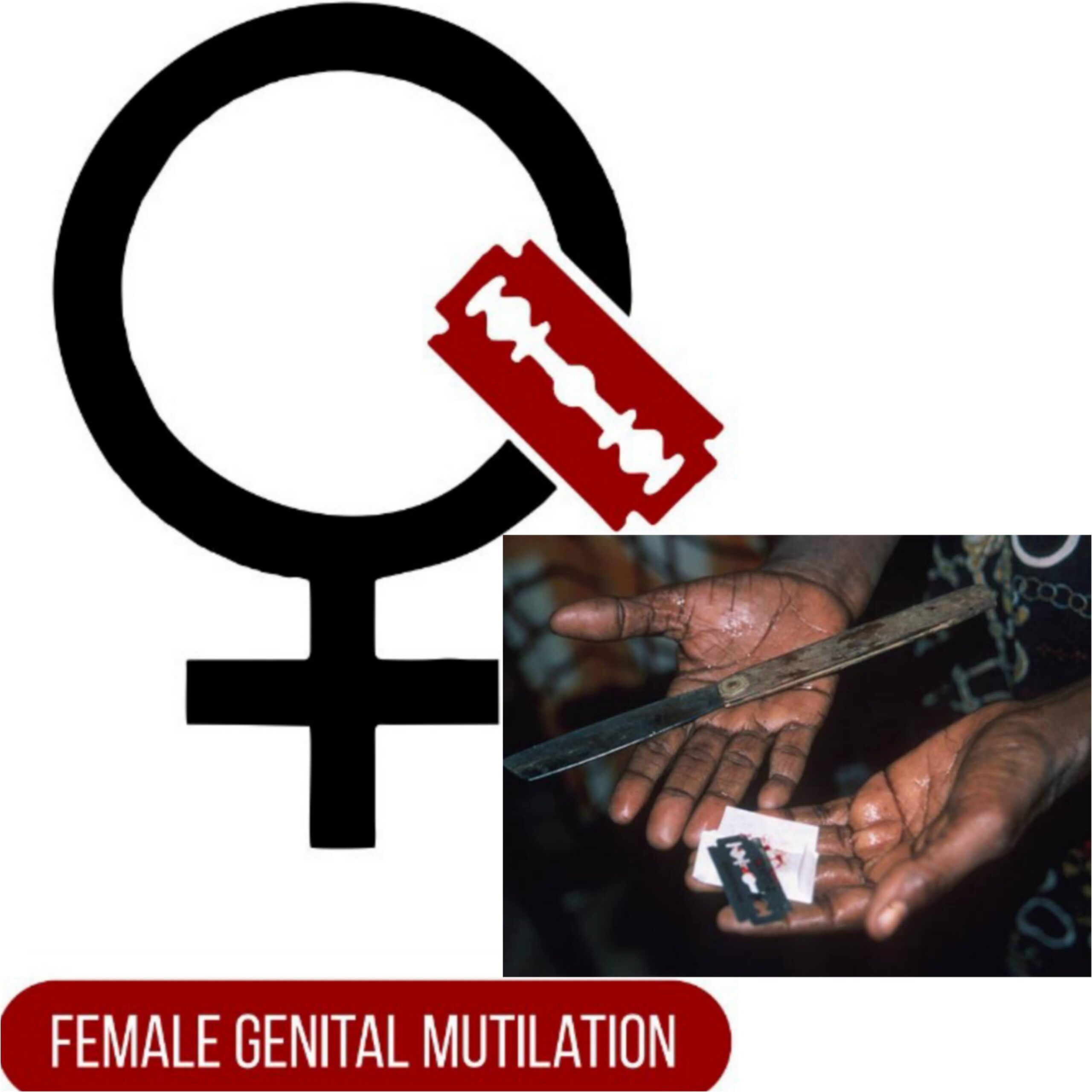

Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), an age-long practice in parts of Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, has continued to rear its ugly head as perpetrators, usually informed by attachment to tradition, have continued to resist campaigns against it.

Recently, the newly appointed Minister of Women Affairs, in Nigeria, Barrister Uju Kennedy Ohanenye, disclosed that the Federal Government will set up a mobile court to try perpetrators of Female Genital Mutilation, sexual harassment and gender-based violence in the country.

Join our WhatsApp ChannelREAD ALSO: Female Genital Mutilation Risks Four-year Jail Term In Edo

At an event organised by Change Managers International Network, drivers of the 100 Women Lobby Group, in collaboration with the Federal Ministry of Women Affairs, Global Affairs Canada, and ActionAid Nigeria, the minister gave details of the proposed mobile courts saying: “Addressing violence against women is a complex issue that requires careful examination, as it involves the participation of both genders. Therefore, I believe that a different approach is necessary to effectively combat it.

“Implementing a mobile court system to address female genital mutilation and the abuse of girls by university lecturers is a significant step in this regard.”

She also said that the president has granted her permission to address the matter. She also said she has had a meeting with the Attorney General of the Federal, who promised that once the Chief Justice of the Nigerian returns from vacation, they can proceed with establishing the mobile.

“We need a mobile court to facilitate our efforts in sensitizing the public about gender-based violence, particularly Female Genital Mutilation as an offence that should not be condoned,” she emphasised.

While mentioning that she would go to the United Nations General Assembly to discuss the matter, the minister urged the citizens to “collaborate and find ways to take immediate action,” against all forms of violence against women.

According to two United Nations agencies – the United Nations Children’s Fund and the United Nations Population Fund, Nigeria accounts for the third-highest number of women and girls who have undergone Female Genital Mutilation, with an estimated 19.9 million survivors.

The two agencies in a statement released in February 2023 during the International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation also said that 4.3 million girls are at risk of FGM this year and the number is projected to reach 4.6 million by 2030.

They warned that the world will miss the target of ending FGM by 2030 if urgent action is not taken to stop it.

For decades, there have been campaigns by various women’s rights activists and groups to stop the practice.

Many women over the years have given accounts of their horrible experiences as a result of having encountered FGM.

“I was infibulated when I was five years old. It hurt so much that I cried and cried. When I was nearly twelve, my aunt one day examined me. They declared that I was not closed enough. They took me to the midwife who lives a few streets away. When I noticed where they were taking me, I tried to run away, but they held me tight and dragged me into the midwife’s house. I screamed for help and tried to free myself but I was not strong. They held me down and put a cover over my mouth so I could not scream. Then they cut me again; and this time, the woman who operated on me made sure that I was closed.

“I don’t know how many days I was lying there. The pain was terrible. I was tied up and could not move. I could not urinate; my stomach became all swollen. I was terribly hot one moment, then shaking with cold. Then the midwife came again. I screamed as hard as I could, as I thought she was going to cut me again. Then I lost consciousness. I woke up in a hospital ward. I was terrified; I did not know where I was. I was in terrible pain; my genital area was swollen and hurt all the time. Later I was told that the infibulation had been cut open to let the urine and the pus out. I was terribly weak, and I did not care anymore. I wanted to die.

“It is years later now. The doctors told me that I could never have children because of the infibulation. Therefore, no one will marry me; no one wants a wife who cannot have a child. I sit at home alone and I cry a lot. I look at my mother and my aunts, and I ask them: ’Why did you do this terrible thing to me?’”

The account above is about a hurtful and traumatizing experience of a Sudanese woman who is a victim of Female Genital Mutilation. She tells her story of how she was forced to get circumcised against her wish. She also shares her pain and the consequences of the actions taken on her against her own will.

As she said, medical experts have told her the sad truth – that she can’t bear children due to the effect of the mutilation that was carried out on her years ago. It is the wish of every woman to carry her child but her own case is different due to Female Genital Mutilation.

Female genital mutilation (FGM) comprises all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), more than 200 million girls and women alive today have undergone FGM in 30 countries in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia where it is practised.

The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) notes that over four million girls are at risk of undergoing FGM annually. But as COVID-19 has disrupted academic programmes of schools that protect girls from this harmful practice, even, more are likely to be subjected to the practice in the coming years. Most girls are subjected to FGM before the age of 15, the UNFPA revealed.

Numerous factors contribute to the prevalence of the practice. Research has shown that the continued practice of FGM is linked to the traditional system that views it as a way of curbing the sexual behaviour of women that negates their morals and marriage, religion, health benefits, and male sexual enjoyment.

Experts aver that in every society where it occurs, FGM is a manifestation of entrenched gender inequality. Some communities endorse it as a means of controlling girls’ sexuality or safeguarding their chastity. Others force girls to undergo FGM as a prerequisite for marriage or inheritance. Where the practice is most prevalent, societies often see it as a rite of passage for girls. FGM is not endorsed by Islam or Christianity, but religious narratives are commonly deployed to justify it.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) describes four main types of female genital mutilation:

Type 1: Clitoridectomy

The practice mostly affects women in East and North African countries. In this practice, the clitoris is partially or completely removed. The clitoris is the most sensitive erogenous zone of a woman and the main cause of her sexual pleasure. It is a small erectile part of the female genitalia. Upon being stimulated, the clitoris produces sexual excitement, clitoral erection, and orgasm.

Type 2: Excision

The clitoris and labia minora are partially or completely removed. It may also include the removal of the labia majora. The labia are the lips that surround the vagina.

Type 3: Infibulation

The vaginal opening is narrowed, and a covering seal is created. The inner or outer labia are cut and repositioned. This practice may or may not include the removal of the clitoris. Other procedures include cauterizing, scraping, incising, pricking, or piercing the genital area, for reasons other than medical purposes.

Type 4

The WHO Trusted Source describes this type as “all other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes” and includes practices including pricking, piercing, incising, scraping, and cauterizing the genital area.

FGM has no health benefits and can lead to serious long-term complications and even death. Immediate health risks include haemorrhage, shock, infection, HIV/AIDS transmission, urine retention and severe pain, complications in childbirth, pregnancy and childbirth, sexual dysfunction, difficulties in menstruation, flashback traumas and infertility.

The treatment of FGM is done through surgery to open up the vagina, if necessary. This is called deinfibulation. It’s sometimes known as a reversal, although this name is misleading as the procedure does not replace any removed tissue and will not undo the damage caused. But it can help many problems caused by FGM. Surgery may be recommended for women who are unable to have sex or have difficulty peeing as a result of FGM and pregnant women are at risk of problems during labour or delivery as a result of FGM.

There is need for the abolition of this unhealthy practice. A multidisciplinary approach involving legislation, health care professional organisations, empowerment of women in society, and education of the general public at all levels with emphasis on dangers and understanding of FGM is paramount.