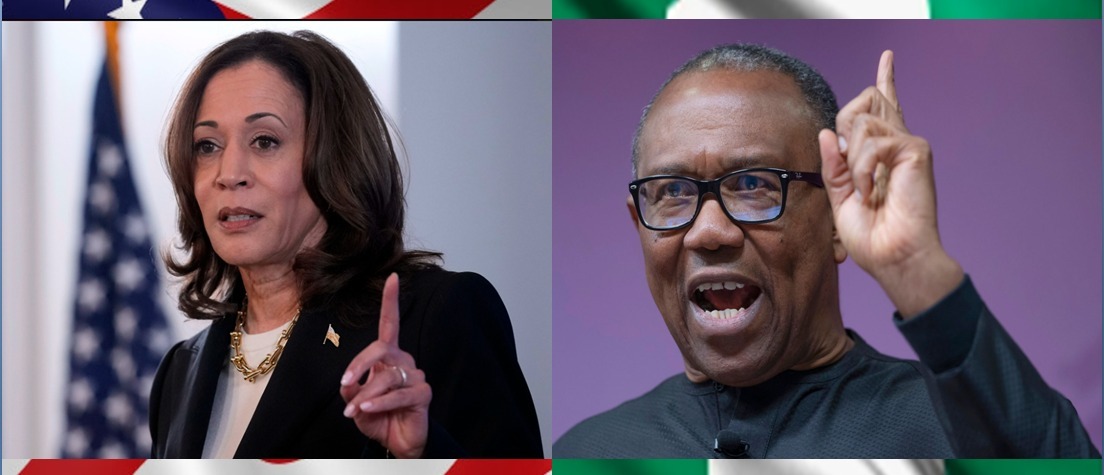

History beckons in Nigeria, if Kamala Harris can smash the power ceiling in the US.

By Chudi Okoye

They are both trying to break a glass ceiling in their respective countries: she, a gender barrier; he, an ethnic one. They are both ‘youngish’ boomers facing septuagenarians who’re well past their prime, being far older than the average age of their countries’ previous leaders. She, at 59, faces an opponent aged 78, in a country with a previous presidential inaugural median age of 55; he, now 63, last year faced and may yet again face a rival who officially claims 72, in a country with a mean age of 50 for its previous heads of government.

Kamala Harris of the United (but quarrelsome) States of America and Peter Obi of (a somewhat disunited) Nigeria are separated by a world of personal experiences. They’ve followed different paths to prominence in public service: she, intrinsically; he, via the private sector. She was district attorney and attorney general in California, US senator and presidential aspirant, before berthing as the incumbent US vice-president. He became governor of Anambra State and was a vice-presidential candidate, before running for president in his own right. Despite their different points of departure, Harris and Obi may be headed for a similar point of arrival as barrier breakers, if providence smiles on them and they also remain steadfast, focused on what they must do to achieve a history that beckons.

Join our WhatsApp ChannelREAD ALSO: U.S. Election: Harris Picks Minnesota Governor As Running Mate

I plan, in this brief excursion, to probe some of the cross-currents, specifically to see what might be relevant in Harris’s foray into the firestorm of US presidential politics, were Obi to re-launch his own presidential bid in Nigeria in 2027. I will look specifically at: (1) how Kamala Harris emerged as the presumptive nominee of her party; and (2) how she’s handling the reactionary forces in US politics, as she rolls out her campaign.

Fortune Favors Kamala

It is nothing short of Shakespearean how Kamala Harris emerged as the Democratic Party’s presumptive nominee for the 2024 US presidential election. To hear her political opponents tell the story, including yarns spun by the Republican Party’s seemingly discombobulated flag-bearer, Donald Trump, the rise of Harris is the result of an intramural conspiracy. They claim that Harris’s principal, Joe Biden, was on course to be trounced by Trump, particularly after his disastrous first debate, and was thus forced against his will to yield the ticket.

There was no indication of subterfuge in the eventual exit of Joe Biden from the presidential race. It was his dismal performance in the June 27 debate, which he and his team had proposed, that proved his undoing. There was certainly a measure of pressure from the Democratic Party hierarchy, alarmed about losing a critical election to Trump, urging the 81-year old to consider whether he had the stamina for what would be an excruciating campaign. While Biden balked at obliging his party, campaign funding – especially from big donors – had begun to dry up, eventually forcing Biden’s decision to quit.

All through the wrenching process, Harris stood firmly by Biden, without the slightest sign of disloyalty to a principal with whom she shared a deep bond. It was her unimpeachable behavior that made possible her seamless transition to the top of the ticket when Biden eventually decided to stand down.

This was crucial because, on deciding to yield, Biden not only endorsed Harris as the party’s nominee, he also orchestrated the transfer of his campaign machinery to Harris – funds, personnel, field operations, etc. This, in turn, gave Harris a great head start. It put her in a prohibitive position against potential challengers, were the party to permit an open primary to choose Biden’s successor, as some were suggesting. With a crunched time to revamp the ticket before the November election, the party alighted on a remote delegate voting arrangement which Harris handily won, having been endorsed by Biden and other party leaders.

It was chance and party pragmatism that occasioned Harris’s hop to the top of the Democratic Party ticket. She deserves great credit, nonetheless, for receiving the baton from Biden and, so far, running a good race.

There is something in all this for Peter Obi. His exit from the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) in May 2022, as the party’s primary loomed, was at the time a subject of some debate. Although Atiku Abubakar was odds-on to win the primary, some felt Obi might again have been made Atiku’s running mate, placing him in a strong position to succeed Atiku in 2027.

There’s little question that PDP would have won the 2023 presidential election, had the party been able to prevent Obi’s departure. Remember that Atiku, under the PDP, secured 29.1% of the votes, while Obi and Rabiu Kwankwaso, both of whom defected from the party, secured 25.4% and 6.2% respectively. These add up to a total of 60.7% won by the three. Although certain statistical adjustments must be made, in reverse-engineering the results, to reflect the incremental effect of the efforts the decampees made to boost their destination parties, a unified PDP would still have won a significantly higher share of the votes than the 36.6% plurality with which Bola Tinubu’s All Progressives Congress (APC) carried the election.

Still, there’s no telling whether Atiku, hankering after the presidency for very long and finally achieving it in 2023, could have been persuaded to walk away from power in 2027. This is where I think, reflecting on what transpired in the US, Peter Obi’s political skills will be tested, if he wants to run again. I am not at all convinced that the Nigerian opposition parties, in their current formation, have a chance of defeating Bola Tinubu’s APC in 2027. I have consistently argued the necessity of a recombination or at least an electoral alliance between the major opposition parties, if they hope to recapture power from the APC (see here and here, for instance). It puzzles me greatly that about a year-and-a-half or so before we enter the 2027 election cycle, there’s been no substantive move in this direction.

A challenge for Peter Obi, if he’s planning another presidential run, is to put Atiku Abubakar – who’ll be over 80 by the next election – out to political pasture. That way, Obi can forge an effective alliance between his Labour Party and PDP. Obi deserves credit for the formidable coalition he built to win a quarter of the ballots in 2023, a threshold no third-party had ever attained in Nigeria’s presidential politics. But he needs a more ruthless step to consolidate his base and turn it into a winning coalition. It starts with sending Atiku into political retirement. For inspiration, Obi can look to how 81-year old Joe Biden was persuaded to hang up his gloves.

Political Force Fields

Persuading Atiku to retire and inheriting his political machine will not be enough to send Obi to Aso Rock, I’m afraid. Even if Obi achieves that onerous task, he will still confront the reactionary forces and frictions of Nigerian politics. There will be atavistic forces threatened by his ethnicity; and there will be conservative forces, even if enlightened, threatened by the progressive and populist tendencies in his coalition.

Obi doesn’t need anyone to tell him that some laws of classical physics, particularly those of Newtonian mechanics, apply to Nigerian politics. The First Law of Motion says that an object at rest will persevere in that state of rest or if in motion will remain on a straight line, unless it is compelled to change that state by forces impressed upon it (F∆t = m∆v). The Second Law of Motion states that the force acting on a body is equal to the mass of that body multiplied by the acceleration (F = ma); as such, the acceleration of an object depends on the mass of the object and the amount of force applied. Both of these laws apply to Nigerian politics, along with the Third Law of Motion which states that whenever one object exerts a force on another object, the second object exerts an equal and opposite force on the first (F1 = -F2).

Obi should contemplate these Newtonian laws, and look to what’s unfolding with Kamala Harris in the US for inspiration on how to navigate the force field of Nigerian politics.

Harris faces a monumental gender barrier in this November’s election. Yes, Hillary Clinton had shattered the ceiling somewhat by winning the Democratic Party nomination and going on to win the popular vote in the 2016 presidential election by a statistically significant margin. She was nonetheless handily defeated by Donald Trump in Electoral College votes (the real decider of US presidential elections), garnering 227 to Trump’s 304. We will see in this year’s election if America will finally elect a woman as president.

Kamala Harris also faces serious racial resistance, although Barack Obama had cracked the racial barrier to US presidency in 2008. The ‘drag coefficient’ of racial bigotry is minimized as a result, but not eradicated.

We can see both of these factors, gender and race, in the particularly nasty politics of Harris’s opponent, Trump. I reported late last month, in the immediate wake of Harris’s emergence as the putative Democratic Party standard bearer following Biden’s exit, that Trump and his party had wasted no time hurling racist and misogynistic abuses at her. I predicted then that it would get worse. And so it has. Trump has mocked Harris’s racial identity; derides her intelligence – calling her “dumb” and “stupid” and “lazy” – all stereotypes used over the years by Whites against Blacks; deliberately mispronounces her name as a form of othering, to give Americans the impression that this woman, born in Oakland California, is not really an American, because she was born to immigrant parents; he even mocks the way Kamala Harris laughs, to invoke the stereotype of African slaves as laughing jackasses; and, in what doubles as a racist and misogynistic slur, he claims that she slept her way to the top.

Donald Trump says these things openly in the media, and on his campaign stops, to roaring laughter and the chortling delight of his supporters. It is all evidence that a significant part of the American population is unwilling to accept the idea that a Black woman can become US president.

Joy Trumps Hate

In Nigeria, of course, leading politicians don’t typically unleash the sort of verbal diarrhea that pours forth from Donald Trump, though their sidekicks aren’t always inhibited. (It is not lost on me that some rank and file Nigerians often appear to be highly enthralled with Trump: no doubt, I imagine – I hope! – because they lack full information about the extent of this man’s baseness.) Whilst reactionary politicians in Nigeria can be more circumspect, they act with no lesser prejudice, as is seen in the lopsided allocation of public goods.

There is a lesson in how Kamala Harris has carried herself in the face of Faustian bigotry. While Trump has been running his mouth, Harris is running her campaign with clout. She ignores his gutter-level baits and insults, or flicks them off with masterclass witticisms, and quickly returns to real issues. She meets Trump’s scowls with wan smiles; his sulking with élan; his grim deprecation of America with optimism. She steers her campaign with calm composure, with poise, with joy and measured exuberance – all of which seem so far to delight her thronging crowds and appear to be driving some positive flutter in the polls.

We don’t know if Kamala Harris can keep this up – all the way to election day. But there’s something to be said for “politics without bitterness,” a slogan adopted by the late Waziri Ibrahim in Nigeria’s Second Republic. Obi has been a practitioner of this type of politics. It is a good way to take bluntness out of the ruthless actions that must be taken to answer the call of history.

Follow Us