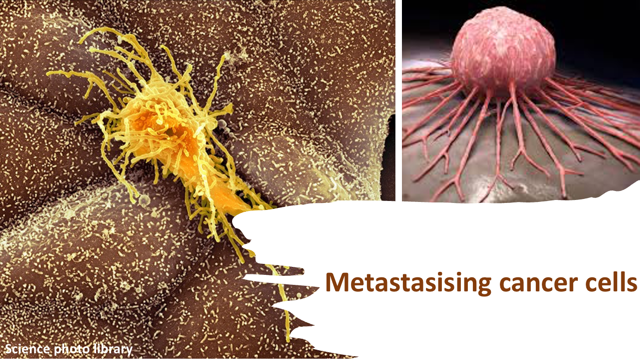

Cancerous cells are cells that grow uncontrollably and have the potential to spread to other parts of the body. Cancer is caused by many factors, including genetic changes, environmental conditions, and the constitutional characteristics of a person. The interaction between these factors or other factors may cause cancer.

It is generally recognised that one in two persons will potentially develop cancer over the course of their lifetime. Cancer moves from one area of the body through the blood to another area in a process known as metastasis. The cancer cells involved in this process are called Circulating Tumour Cells or CTCs.

Join our WhatsApp ChannelThe thinking is that CTCs are constantly released from growing tumours, but it appears that this may be wrong. Recent work done by Aceto and coworkers, which was published in the June 2022 edition of the journal, Nature, did show that metastasis is influenced by circadian rhythms.

Circadian rhythms or clocks (i.e. the body’s cycle of daily rhythms) are natural processes like physical, mental, and behavioural changes, which respond to light and dark. The rhythms control your body so that you go to sleep at night and wake up at daytime. The circadian rhythms affect not only humans, but also animals, plants, and microorganisms.

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) in 2007 classified shift or odd-hour jobs as circadian disruptive factors that could lead to human carcinogen. People engaged in shift jobs such as night nurses, security guards, healthcare workers, etc., are more likely to develop cancer because their circadian rhythms are chronically disrupted (i.e. chronodisruption). Several epidemiological studies have identified the disruption of the circadian clock as a contributory factor to accelerated onset of cancer. It is also well-documented that short-term chronodisruption, for example, when you take a long haul flight, or party all night, results in health issues like insomnia, fatigue, lack of appetite, mood swings, impaired performance, etc. For a long haul flight, the experience of fatigue or impaired performance is commonly known as jet-lag.

Aceto and coworkers found that the circulating tumour cells or CTCs are more likely to enter into the bloodstream at night while the patient is asleep and travel to another part of the body to establish a new cancer “colony” than it would during the day. This process of cancer cells passing through the wall vessel and entering into the blood is called intravastation. The study also found that CTCs generated during the night have higher proclivity to metastasise, but those generated at daytime do not. This tendency for CTCs generated during the night to metastasise is not a continuous process but only limited to when the person is resting at night.

The researchers were surprised at first when they were studying the process of metastasis in mice, to notice that the levels of CTCs in mice with tumours differed significantly depending on the time of day the blood samples were collected. To solve this phenomenon, they collected blood samples from 30 women suffering from breast cancer at 4:00 a.m and 10:00 a.m, respectively. At the time of the blood sampling, 21 of these women were diagnosed with early breast cancer (ie no occurrence of metastasis, yet), and nine were diagnosed with stage 4 metastatic disease. The analysis of the blood samples, showed that 78.3% CTCs were present in the blood samples collected at 4:00 am during the rest phase of the patients.

The researchers decided to test the generality of these concepts by grafting breast cancer tumours into mice. The result was that the CTC levels were highest during the day when the mice were resting, by as much as 88%. Remember that mice are active at night than during the day. In other words, they have an inverted circadian rhythm compared to humans.

In order to characterise the metastatic timing events, samples of CTCs were collected from mice both at rest phase (day time) and active phase (night time). The samples were labelled with fluorescent tags before injecting them back into the mice. The CTCs that develop into new tumour cells were from samples collected when the mice were at their rest phase; thus, suggesting that the CTCs underwent metastasis better at rest phases than during active periods.

Hormones, which respond to circadian rhythms such as melatonin (secreted in the brain and controls body sleep), testosterone (sex hormone for libido), and glucocorticoids (involved in the conversion of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats into useful energy), including insulin, influence the generation of CTCs resulting in the proliferation of cancer cells, depending on when these hormones were administered.

READ ALSO: New Cancer Vaccines Raise Hope

The findings in this study do not mean that cancer patients should be deprived of sleep. On the contrary, for it has been shown that people with cancer who get less than 7 hours of sleep at night are at higher risk of death than those who get more sleep. Therefore, the study amongst other things, served to highlight the importance of collecting cancer clinical samples at specific times (ie during rest phases) when the circulating tumour cells are at peak levels in the blood, which for humans is at night time, and for mice during daytime.

The study also reinforces an earlier discovery in 2018 that synchronising drug delivery with a patient’s body clock can yield clear benefits. A new thinking in disease treatment called chronomedicine or chronotherapy believes that timing rather than drug dose is more important in the treatment of a disease. In effect, treatments given at specific times of day work better than treatments administered randomly. This type of treatment takes advantage of a patient’s circadian cycle to minimise side effects while maximising the therapeutic benefits.

Follow Us