For manufacturing in Nigeria, access to funds is central to acquiring the right technologies, human resources and to fully utilize production capacity. In addition to any other source of capital, businesses are expected to be able to access bank loans at rates comfortable to borrower and lender. This is crucial for both to operate on a reasonable profit margin without necessarily endangering investments or bank deposits.

However, there are concerns that, over the past decade, Nigeria’s manufacturing sector has not got a fair deal from banks. The manufacturing sector accounts for only about 10% of economic activity or 7% of government revenue. Refined petroleum products are imported and subsidized, putting enormous pressure on crude oil earnings, and turning the country into a serial borrower.

Join our WhatsApp ChannelREAD ALSO:Manufacturing Trade Deficit Hits N2.6tn Despite Forex Shortage

Interest rates, tough bank requirements, inflation and exchange rate volatility in official and unofficial markets make it hard for manufacturers to receive credit from banks. Earlier in the year, the Manufacturing Association of Nigeria (MAN) decried banks’ penchant for short term loans that do not meet the basic requirements for medium and long-term investments. This adds to the burden of high cost of erratic electricity supply, high cost of fuel, high exchange rates and reducing demands for products.

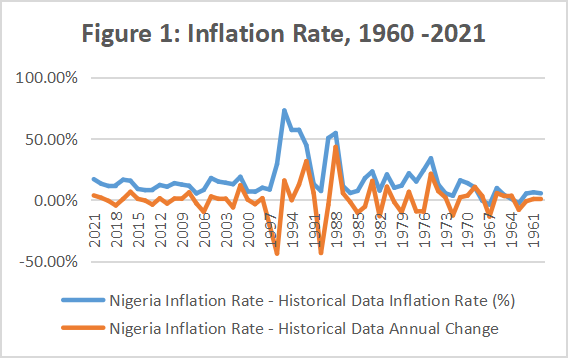

Citing CBN sources, two researchers, Uchechi Taiga and Ilemona Adofu had noted that Nigeria’s inflation rate rose from 11.8 percent in 2010 to 11.98 percent in 2019. In the same vein, exchange rate rose from 150.4 percent in 2010 to 360.25 percent in 2019; this also resulted the lending rate rising from 22 percent in 2011 to 30.72 percent in 2019. Between 1960 and 2023, inflation in Nigeria rose from just above 5% to 16%, having peaked to 44% as of 1992 (Figure 1). At its current stage, Nigeria’s inflation rate is the 4th highest in Africa after Zambia (22.02%), Angola (25.75) and Sudan (382.82%).

Experience has shown that the vacillation between fixed interest rate (by the CBN) and a deregulated interest rate (determined by market forces) between 1986 and 2019 has not brought down the interest rate below 20%. The researchers offer a simple instance: given the interest rate of 22%, a producer of tomato paste who requested a five-year loan of ₦1 million, is expected to pay back with the total sum of ₦1.22 million, and with the interest rate of 30%, the manufacturer is expected to pay back with the total sum of ₦1.3 million.

The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) in March 2023 raised interest rates to 21.91% (a 17.5 year high), up from 21.82% in February, even beating market expectations of 21.85%. The CBN cited exchange rate pressures and an expected removal of fuel subsidy as its reasons for the hike. Despite the situation, Nigeria’s economy recorded a growth of more than 3.52% in 2022 relative to the 2.25% rise in the third quarter of 2021. The growth was noticed mainly in the services sector rather than the manufacturing sector. By implication, while the main operators in the services sector such as banks are declaring profits, the manufacturing sector that banks should primarily support are lagging.

Banks in Nigeria recorded an aggregate 26% increase in their profits in 2022 compared to 2021 earnings. The increase is largely a result of the regularly increasing interest rates from lending. In monetary terms, the aggregate bank profits in Nigeria rose to ₦3.13 trillion ($US 6.6 billion) up from ₦2.48 trillion in 2021. MAN, by contrast reported a 15% contribution of the manufacturing sector to Nigeria’s GDP in 2022, implying a negative growth rate of -19% compared with the 2022 figures. However, the manufacturing sector’s $64.41 billion output for 2021 was a 17.65% increase from 2020. The negative growth has further been linked to brain drain, tying up of investments by multinationals, the war in Ukraine and cost of diesel. MAN reported a whooping ₦67.7 billion spent on diesel in the in the first half of 2022. Officially, the naira to dollar rate stands at ₦461 to the dollar, while the parallel market hovers around ₦752 to the dollar.

The failure of interest rates to have a significant positive impact on the manufacturing sector means that some measures have become important. The first must be to redress what some have described as an arbitrary multiple currency exchange systems, in which the so-called black market becomes the real currency exchange system rather than governments approved exchange rates. The new government of President Bola Ahmed Tinubu has unified the exchange rates. But whether this is enough or done properly is a matter for another day.

READ ALSO: 10 Gains Of CBN’s Exchange Rate Unification – CPPE

The deregulation of the interest rate policy should be monitored to avoid interbank collusion to shortchange industrial borrowers. Such monitoring oversight can be made into a legal instrument mandating bank to devote a certain percentage of their deposits to financing the manufacturing sector. As it is, the CBN requires banks to lend it (CBN) money when they (banks) have excess cash. This is the same cash that other banks can borrow from the CBN to offset cash pressures, especially when borrowers call. Curiously, findings show that while the amount of cash lent to the CBN by banks continues to grow, the amount lent to the manufacturing sector by banks continues to decrease. As of March 2023, the CBN recorded a first quarter bank lending of N641.19 billion, while banks have only accessed ₦453.7 billion.

Exchange rate safety nets, improvements in the energy sector (electricity and local crude refining) and subsidization of the importation of raw materials should be undertaken by the federal government to reduce manufacturing costs. Even banks incur costs from these areas, which are eventually transferred to borrowers, causing further rise in interest rates. Multiple taxation, reducing insecurity and supporting the local production of raw materials are other ways canvassed by MAN which the federal government needs to uphold in action. I insist that a situation where banks are declaring high aggregate profits, while the manufacturing sector is declining presents an inexplicable economic paradox.

Dr Mbamalu is a veteran Journalist, Editor and Publisher

Follow on Twitter: @marcelmbamalu

Follow Us